Viral portraiture

David Goodsell's mesoscale molecular landscapes, and the uncanny vitality at the edges of life

Of all things—a scene that has stayed with me, from the late ‘70s TV series The Incredible Hulk, since I saw it as a ten-year-old: Bill Bixby’s David Banner, the scientist who is Hulk’s mild-mannered embodiment, has fallen in love with a terminally-ill psychiatrist, played by Mariette Hartley. Banner has identified the disease attacking her cells’ mitochondria; using her pioneering hypnosis technique, they now visualize her cells rebuffing the pathogen’s attacks. After a hypnotically-induced voyage through blood vessels and microscopic cells, Hartley’s psychiatrist confronts the intracellular site of illness using imagery from western-movie serials of the mid-twentieth century: her mitochondria become a wagon train; the disease a band of “renegade Indians”; cellular settlers firing from cover; medicine arriving in the form of cavalry to save the day.

The image is fraught, to say the least—fraught, and telling: the body figured as territory to be claimed and defended, a settler-colonial imaginary where claims are staked by an array of forces—pathogens, medicines, techniques of transformation and care—and the subject herself a migrant lacking clear title. None of this occurred to my ten-year-old mind, of course. But I was struck by the uncanny magnitudes, the body as cosmos, the powers-of-ten sublime of intracellular space. I was struck by the labor of visualization, too: Bixby & Hartley peering through microscopes , mixing cell-stuff up in glassware, staining slides, taking turns in the hypnotist’s chair.

Bixby and Hartley’s moves came to mind last week with the publication of David Goodsell’s imagery of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. Vividly different from 1970s made-for-TV hypnotic ideation, Goodsell’s vision recalls the aesthetics of an earlier decade with its swarming colors and psychedelic profusion of forms. But there’s much more at work here than the Peter Max-inspired palette might suggest, and it’s worth unpacking Goodsell’s practice.

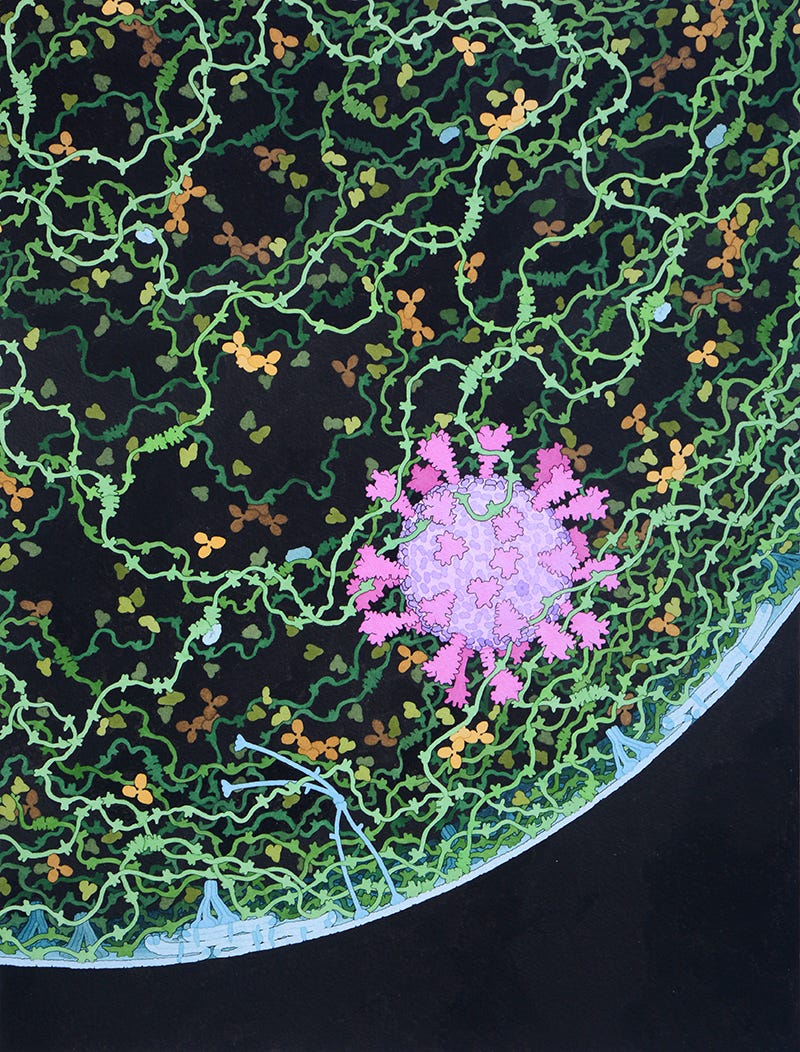

What are we seeing? The central figure is a particle of vaccine, and though it looks alive, it’s a made thing: in cross-section, a spherical capsule of lipids (light blue) studded with protective chains of polyethylene glycol (the green strands), sheltering a wormy tangle of RNA encoding the coronavirus’s spike protein. The earth-toned granules in which this uncanny contraption nestles, meanwhile, represent glycoproteins, cholesterols, immunoglobulin—molecular constituents of blood plasma, which is not fluid at this scale but granular, tense with a tangle of energies.

Goodsell describes these paintings—for paintings they are, made in watercolor—as “mesoscale molecular landscapes.” What we’re seeing here isn’t phenomenally “visible” in the ocular sense—visible light can’t resolve images of objects at this scale. The visual realm expressed here is a synthesis of diverse ways of seeing and knowing at molecular scale, drawing from a long genealogy of imaging technologies, from x-ray crystallography and electron microscopy to computational modeling.

Goodsell’s “Meso-” names the betwixt-and-between world where viruses and vaccines meet: larger than protein folds and electron shells (visualizing at these scales is another craft), but far smaller than the spaces occupied by cells and tissue structures. “Landscape,” meanwhile, recalls the territorial metaphor from the Hulk, evoking spatial imaginaries that have patterned much modern medicine. “Landscape” feels like understatement, however, in these images that depict molecular happenings with cosmic grandeur. Take Goodsell’s rendering of the realm of the respiratory droplet—a superplanet at 5 μm in diameter, a cotton-candy-colored coronavirion tangled in meridional strands of mucin:

Or this sectional slice through infected cell machinery efficiently cranking out new virions, packing freshly-minted RNA genomes into protein-studded envelopes:

Goodsell’s watercolors inhabit the 21st century paradigms of precision medicine and bioengineering, where ribosomes are manipulated computationally, constituents of life made to swirl and stitch, transcribe and encapsulate, with their own distinctive industriousness. And yet something in Goodsell’s work also exceeds this paradigm. These vibrant images are haunted by their own impossibility, their alienness, their estrangement from all of our metaphors and models. Life at mesoscale is irreducibly weird, irreducibly other. I think of Elizabeth Povinelli’s conception of the Virus as an archetype haunting the Anthropocene: a “figure of geontology” which, alongside the Desert and the Animist, comprises the patterns of “late liberal governance.” Povinelli’s Virus is “the figure for that which seeks to disrupt the current arrangements of Life and Nonlife.” In Goodsell’s paintings, I sense that arrangement unsettled, quivering, subject to metabolic disordering; I sense that the border between Life and Nonlife is vital in the arrangements of living systems. Sensing it in my own cells, I know that circling the wagons is no longer the most salient metaphor; something more like entanglement, symbiosis, and acceptance is called forth.

Beautiful scale-shifting.