I was scrolling through Instagram Sunday morning when a short video caught my attention, of 14-year-old Wendy Lou Holcombe playing her banjo for an aged woman in a nursing home (via @dimestoreradio on Instagram). Holcombe, a country-music prodigy of the late 1960s and 70s, asks the elderly woman if she’d like her to play a tune, and the woman says yes; Holcombe glances at her fretboard conspiratorially, sets her tongue in her teeth, and launches into a riffling version of “Cripple Creek.” Over the spillway come the notes, and the shot cuts from Holcombe’s intent and relishing face to the aged woman tapping in time on the arm of her wheelchair. As the music peals on, the woman folds her hands, looks aside, seems to go inward. Holcombe finishes the tune, stops the strings into silence; she shuts her eyes, riven by the passing of some fleeting thing; she reaches out and lays her hand on the woman, and then bends in to kiss her on the cheek and embrace her. Do you love me? the woman asks in a welling, cracked voice; oh yes ma’am, Holcombe whispers, her own voice hushed, overwhelmed. Then tell me what to do with myself. I don’t know what to do with myself, you tell me what to do.

This moment holds so much—Holcombe’s preternatural music and presence, of course, and the generosity and relish with which she offers it. Much more, her deep, intuitive response to the older woman, her own great emotion apprehending the woman’s state in the midst of the music. The elderly woman’s question, naked and brave: do you love me? Moved by the music, the flung-open treasury of the music, its great beauty and purity, a priceless thing freely given, the old woman overcoming some heartbreaking incredulity to arrive at love as the only possible reason for this bounty. And then her appeal: tell me what to do with myself. Stripped of her powers she seems, denied even the powers of elderhood, and bereft; and in the circle of beauty made by Holcombe and her music, she feels the presence of a divine power, a wisdom, a welling.

Tell me what to do with myself. I’ve listened to my mother make similar appeals from her nursing-home chair, and have found myself disconcerted at the poverty of my reply, confounded for anything like an answer. There is a distant cock’s cry in these moments that I can’t shut out.

The social-media clip of Wendy Lou Holcombe is taken from the first episode of Big Blue Marble, a series for children that aired on public television beginning in 1974. I remember watching the show, each episode of which consisted of several segments profiling young people living here and there around the world. I don’t remember viewing Holcombe’s segment as a child, though I doubt I could have seen in it then what I see now.

Holcombe’s visit to the Briarcliff Nursing Home begins at about 14:25 in the episode, below. Before Holcombe plays, she asks the old woman for a verse, and she recites both “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” and “Yes, Jesus Loves Me.” The words come through great effort, shorn of melody, and yet I suspect their music rang for her.

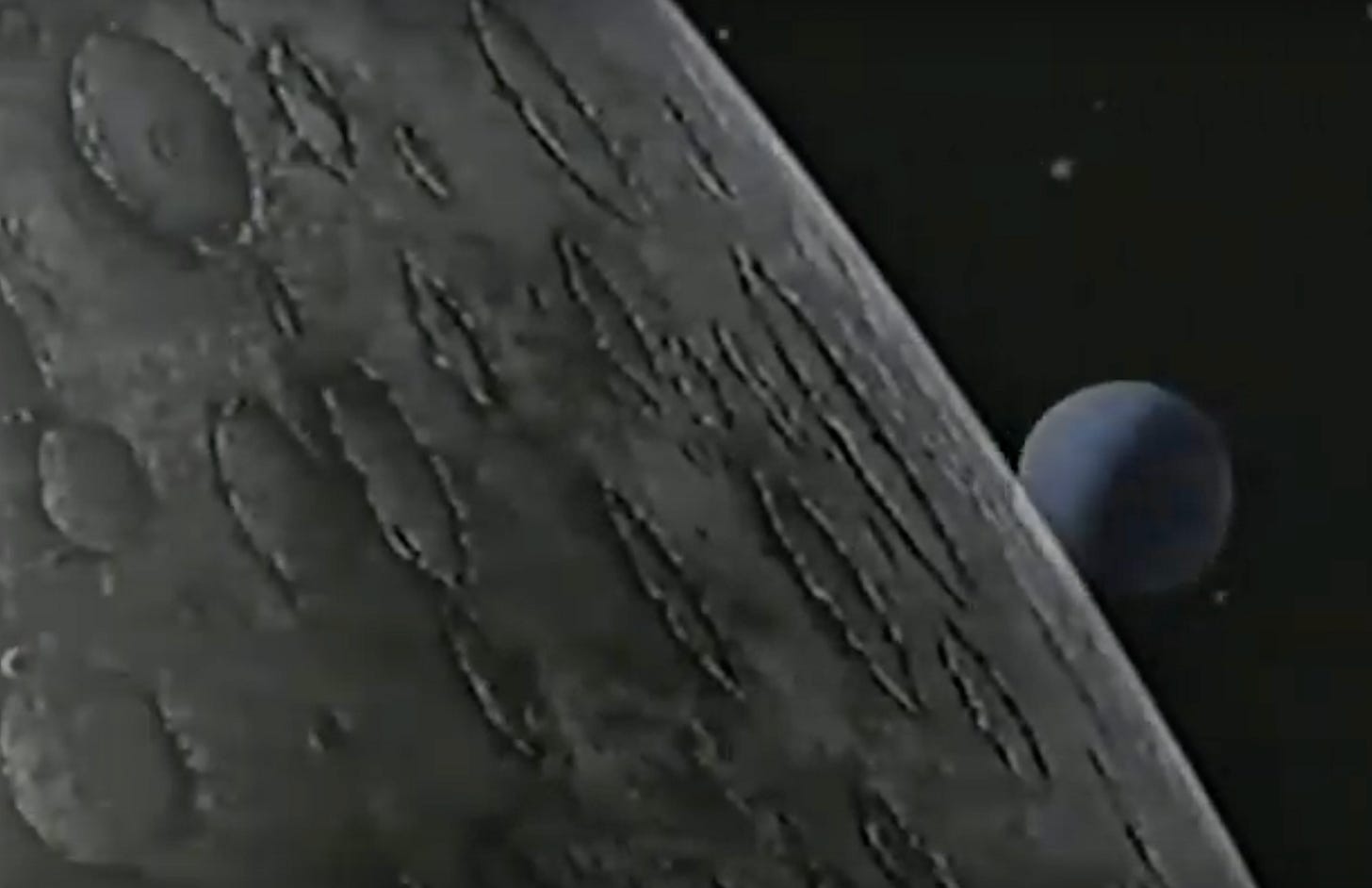

Twinkle, twinkle, little star. Each episode of Big Blue Marble opens with an image of the earth passing behind the surface of the moon, its craters and gray blankness filling the screen and then sliding away to reveal the earth again, reprising the “Earthrise” photo taken during the Apollo 8 lunar orbital mission of December, 1968. Strings swell, and a singer’s voice cuts in—The Earth's a big blue marble when you see it from out there—as we zoom into a closer view of the earth before cutting to scenes of young people engaged in work and play around the globe.

I was born during the Apollo 8 mission, and so Earthrise always catches my eye; the imagery now hit me with special force, as astronaut James Lovell had died a few days earlier at the age of 97. Better remembered for his role as commander of the Apollo 13 mission, Lovell also was a member of the Apollo 8 crew, alongside Bill Anders and Frank Borman. I love the audio recording captured on board from the moment the Earthrise photo was made: Anders catching first sight of the earth appearing from beyond the moon and exclaiming in wonder; Lovell’s husky voice murmuring, oh man; Anders urgently pestering Lovell to pass him a camera loaded with color film as the spacecraft moves and the view shifts from one window to the next, Lovell eager to take the picture: I’ve got it right here, Bill! while an impatient Anders barks now calm down, Lovell, calm down! In this moment, the spacecraft is still coming out of the far-side half of its lunar orbit, not yet in radio contact with controllers back on earth, and the astronauts are able to let down their professional mien and be wanderers, wonderers, camera bugs angling for the shot.

In retirement, Jim Lovell headed several technology and manufacturing firms; Ron Howard’s 1995 film about the Apollo 13 incident brought renewed fame, and he became an affable public voice for the history and the significance of the Apollo program. Bill Anders, who took the Earthrise photo, died in 2024 at the age of 90 when the single-engine plane he was piloting crashed into the waters near Orcas Island in Washington.

Were there ever moments in their later years when even such men as these—renown, decorated, massively accomplished—asked, what am I to do with myself?

Wendy Lou Holcombe died from a congenital heart condition at the age of 23. I see the moon, especially when it is full as it is now, and I think, that’s what 200,000 miles looks like. But now I wonder if the distance spanned by Holcombe in that moment in the Briarcliff Home was somehow much greater.

https://open.spotify.com/track/1bne4gsJshCv77LeKqQb1A?si=d5A-WmHZQISHpqjJGmhbpw

Agree with Kirk