How to save a ghost

Widening circles of self and story

It was a dense, heartsore-humid morning when I arrived at my mother’s assisting-living home last Sunday. From the parking lot, I could hear the angry back-and-forth of three men about my age, brothers presumably, who huddled on the porch in the heat of sacramental call and response: This is ruining my life—Well, you get a fucking medal then! I approached on soft feet, willing myself invisible, and pressed the buzzer, but no one was there to open the door, and so I retreated to the shade of the maples on the big lawn and dizzied myself watching the ground bees skim in low, eccentric circles over the grass. While sitting there, I called my wife, Rebekah, and as we talked about sickness and health and the brothers quarrelled, I felt a tremor rise and root in my chest.

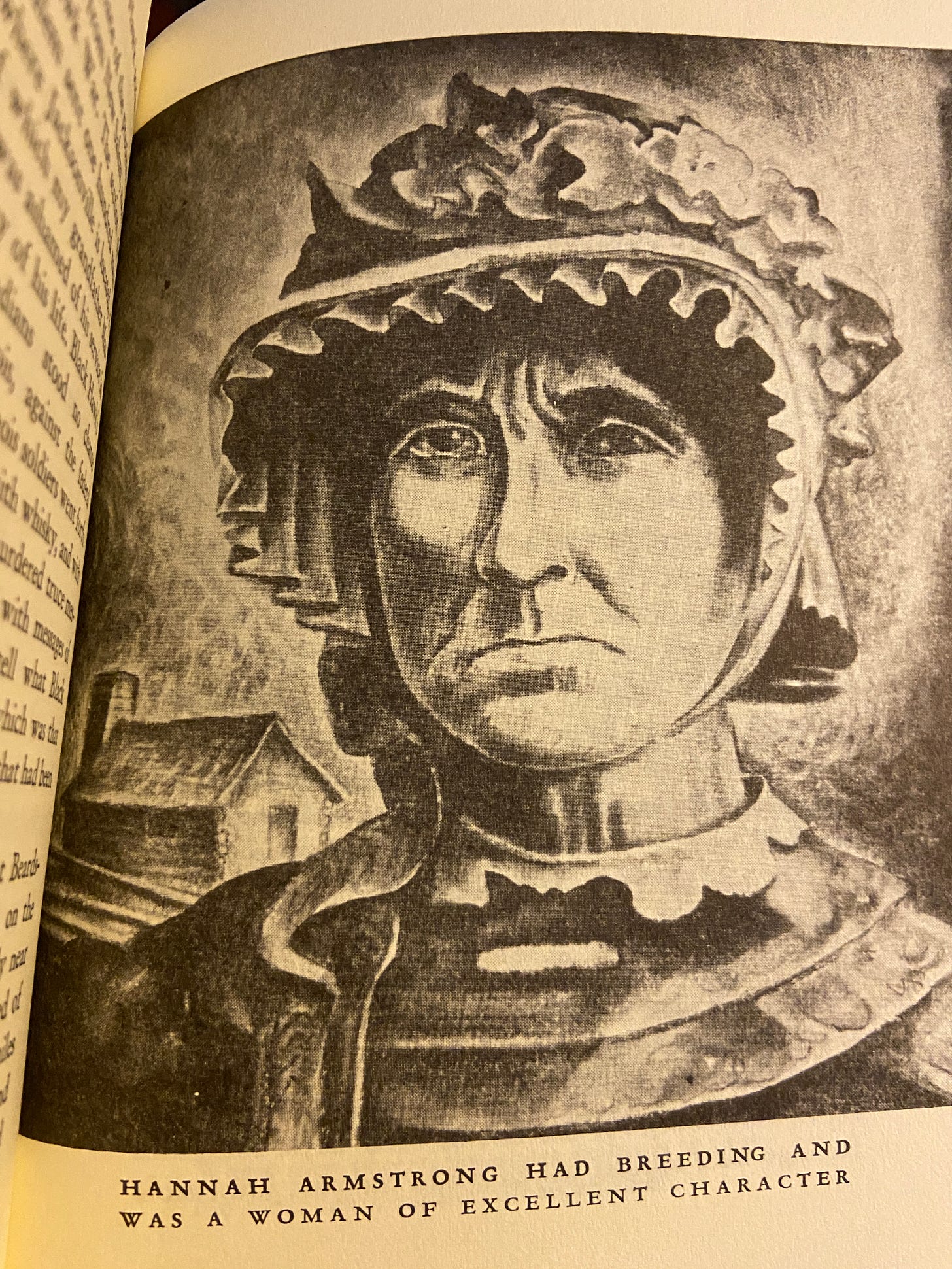

The brothers dispersed to their cars, the grounds quietened. When my call ended I went back to the door, where a woman in a green apron sitting under the liftgate of her Subaru smoking a cigarette saw me mashing the button and came over with a fob to let me in, drawling about membership and its privileges. Inside, I found my mom dozing in front of her television, where Little House on the Prairie had been running in continuous, episode-by-episode download the last few days. In the episode playing as I arrived, Mrs. Olsen’s lies were getting out of hand, and the Ingalls children were fixing to teach her a lesson. I quietly took a seat, watching Laura’s bonnet waggle as she ran off to exact her justice, and thought of Hannah Armstrong. I’d recently picked up The Sangamon, the poet Edgar Lee Masters’ book about my home region, and it had fallen open to an arresting drawing of Armstrong, who figures in Masters’ more famous Spoon River Anthology. A sounding of the dead, Spoon River comprises a chorale of testimonies, recollections, and excuses from the grave. Many of Masters’ sources for those poems lived in my hometown and the surrounding area.

In Spoon River, Armstrong recalls a visit she paid to Abraham Lincoln in the White House, where she travelled to secure the discharge of her son from the Army:

And when he saw me he broke in a laugh,

And dropped his business as president,

And wrote in his own hand Doug's discharge,

Talking the while of the early days,

And telling stories.

Her portrait in The Sangamon offers us a frank burl of a face framed with a Little-House bonnet of petalled crenellations; the caption reads, “HANNAH ARMSTRONG HAD BREEDING AND WAS A WOMAN OF EXCELLENT CHARACTER.”

When it was time for my mom to go to lunch, I left and drove out to visit my father’s grave in Oakland Cemetery, where Edgar Lee Masters also lies. It’s a twenty-mile drive over the plains, the long-period blink of corn and beans, corn and beans, varying where the creeks meander here and there across the Jefferson grid. As I drove out of town and up into these horizons, the phone call came back to mind, my breath started to catch, I felt the quaver blossom again in my chest. First subtly and then all of a sudden, I felt the words come: I am a ghost. I am a ghost. I felt inescapably like an invisible presence hurtling over the fields, untouchable and untouching.

I called Rebekah from the road, and our talk dispelled the panic but not the haunted ideation. Later, my teacher reminded me of the koan, “Save a ghost,” one of the so-called miscellaneous koans of the Zen tradition, which is haunted by “hungry ghosts” who carry into death the burden of their appetite—for money or food or sex; for happy talk or self-regard; for solace. Most of the characters in Spoon River are hungry ghosts; Hannah Armstrong is one of the few exceptions. But it was another ghostly condition that had struck me as fear and grief wrapped itself around me on the road: not hunger, but disconnection. Being without becoming, the story going on without me. The story, the story, of all I hold dear; of all those who through grieving will come to get on with it; of projects and prospects and deeds and deliverables. Corn and beans, corn and beans, sown and grown without me, without me, as I hurtle along endlessly untouchable and untouching.

I say “not hunger but disconnection,” but is there really any difference?

At the cemetery, I placed a stone on my dad’s grave and another on behalf of Rebekah. Dad’s grave is in an open area, along with many of the newer plots, beyond the eaves of the trees that canopy the older graves. I retreated to their shade, sitting on the roots of an old sweetgum while the wind played in the grass, feeling its way into the underbrush that crops up at the edge of the cemetery. It was a gentling wind, an easy wind, and it coaxed me into curiosity. I wandered over toward Masters’ grave, passing names of parents of childhood friends; the name of a classmate, felled last year by the chronic illness that had stalked her even in high school; names I know from tire shops, insurance companies, and farms up and down the Sangamon and in and out of town.

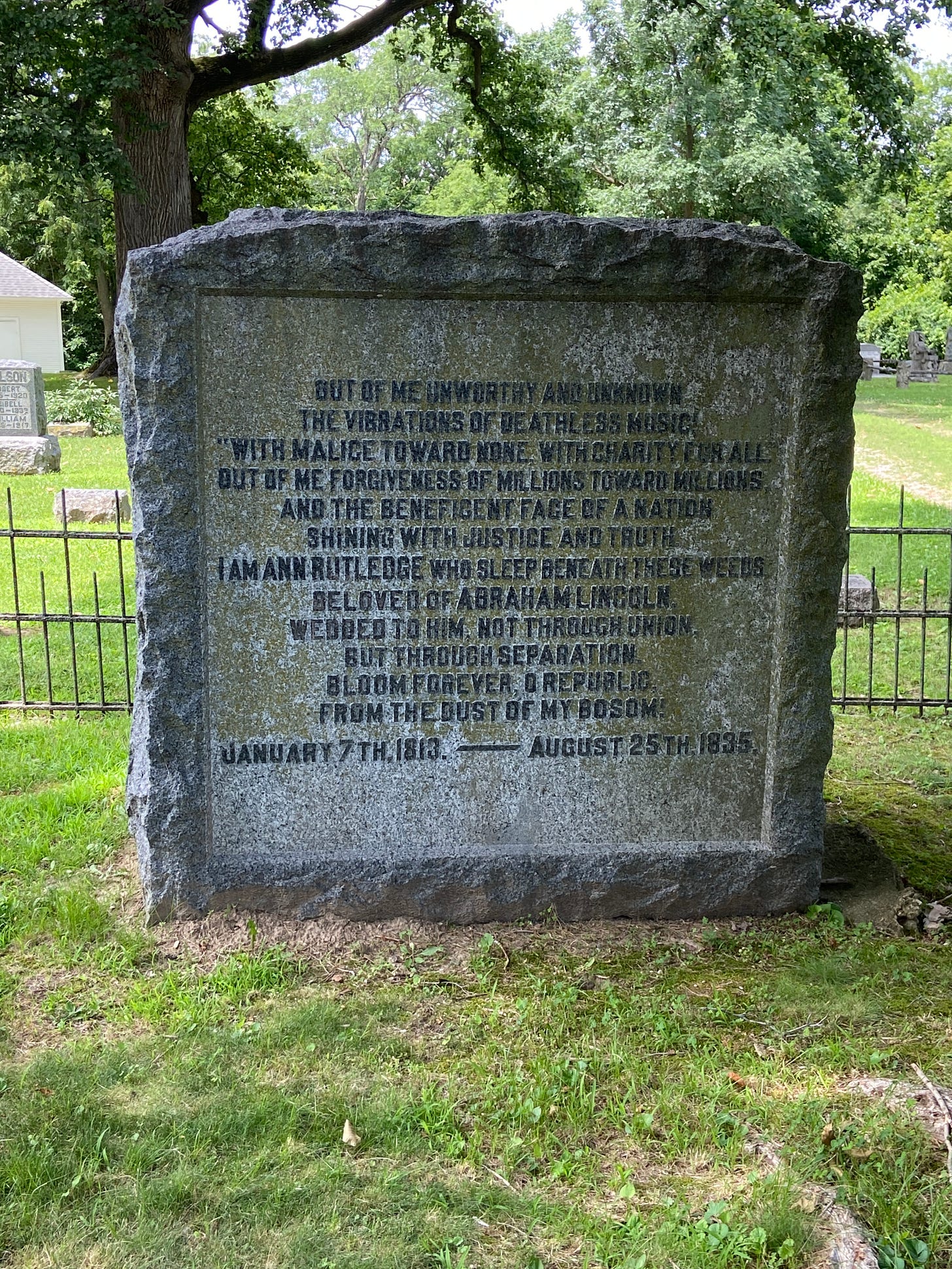

Masters’ grave is marked for pilgrim tourists by a bright blue sign, and as I made my way toward it, I stopped by another one so marked: the burial site of Ann Rutledge, who also appears in Spoon River. The supposed first love of Abraham Lincoln, she died young, before Lincoln’s rise. Masters’ poem, carved on her memorial as an actual epitaph, imagines her demise as a kind of civic apotheosis: “Bloom forever, O republic/From the dust of my bosom!”

I have visited Ann’s grave many times; I feel no hunger there. There’s a vague disquiet, but it doesn’t belong to Ann. This time, I thought of myths that turn women into trees to escape the hungry ghosts known as gods. What a metamorphosis Masters lays on Rutledge: from her dust, no tree, but a nation! I found myself wanting a word from one who could dispell this burden, who could sing a release from the poet’s strange appetite.

Turning from Ann’s fenced grave, I caught sight of a third blue sign beyond Masters’:

Hannah Armstrong! I had never known or else had forgotten that she is buried here, too.

With Hannah, no hunger, not today. Only the wind, the trees, the birdsong, and the clement, midsummer silence of the lands sloping away to the river beyond, a silence buoyed by the green crackle of growth subliminal. The silence of all these names, these ancestors, shaken loose from the hungry epitaphs, not roused to reckless, untouchable flight, but rising in widening circles of fruitful solace. And in the sangha of the ancestors, I felt the caress of a story—or maybe not a story, but a great song—which doesn’t go on without me, but in which I’m already incorporated.

Save a ghost.

You found the right words in the right order, Matthew. This is such a moving, tender, stunning piece.

Hauntingly beautiful